The #1 Best Thing You Can Do For Weight Loss

Do you struggle with getting weight off and keeping it off?

Arguably, the biggest challenge with weight loss, is sustainable progress.

In this article, you’ll learn the best steps you can take towards sustainable weight loss while referencing some of the longest fitness related research studies done to date.

First, The Basics of Valuing Research Studies

Many people reach conclusions just because they read one research summary. But the real value of research isn’t just in its mere existence. There are a lot of factors that make research solid, and some of it can seem pretty foreign to anyone outside the professional field.

In general, here are some key things that make research good:

- Sample/Test Size: How many people were tested? A study that looks at 8 men and 8 women is generally a lot weaker than one that looks at 20,000 men and 20,000 women.

- Bias: Were the participants already fit? Did the study include a wide variety of fitness levels? A study with a bigger, more diverse sample size usually leads to more reliable conclusions.

- Time: How long did the study last? A study that runs for 2 years tends to carry more weight than one that only lasts 6 weeks.

- Repeatability: This is probably one of the strongest signs of a solid study—have other researchers been able to replicate the results? If similar findings show up across different studies, it adds a lot of credibility.

While we’ve covered some key factors that contribute to solid research, there are additional factors to consider, like study design, peer review, and funding.

For more information, check out the section on ‘Additional Factors to Consider in Valuing Research’ at the end of this article.”

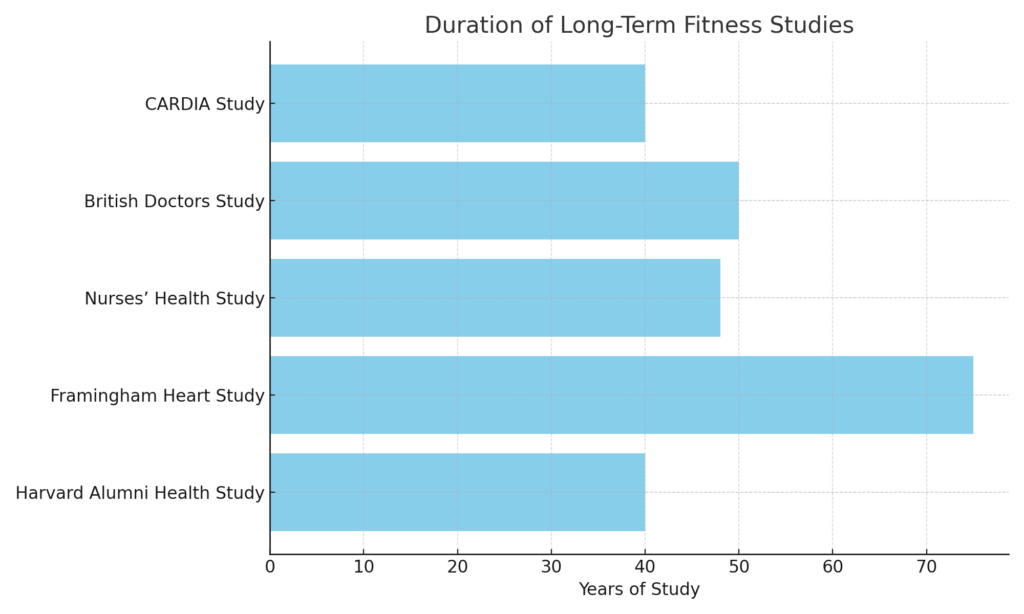

Now that we’ve got a general idea of what makes research valuable, here’s something cool: there have been several fitness-related studies that have gone on for 50+ years! There’s a lot we can learn from them—or at least be reminded of.

The Harvard Alumni Health Study

- Time: 1960s through the early 2000s

- Size: 17,000 males

- Some Key Findings:

- Men who engaged in moderate to vigorous physical activity (burning approximately 2,000+ calories per week) were significantly more likely to maintain their weight over time compared to sedentary individuals.

- Regular exercisers gained less weight with age, particularly those who consistently walked or performed other moderate activities for 30+ minutes a day.

Framingham Heart Study

- Time: 1948-Present!

- Size: Over 5,000 following multiple generations or residents in Massachusetts

- Some Key Findings:

- Participants who engaged in regular moderate to vigorous physical activity were 50% less likely to experience significant weight gain over time compared to sedentary individuals.

- Individuals who maintained consistent exercise routines had a 30% lower risk of becoming obese over a 20-year period, highlighting the role of physical activity in long-term weight management.

Nurses’ Health Study

- Time: 1976-present!

- Size: Started with over 120,000 female nurses!

- Some Key Findings:

- Women who consistently engaged in moderate-intensity exercise, such as walking briskly for 30+ minutes per day, gained less weight over time compared to those who were less active, particularly after menopause.

- Women who increased their physical activity to 60 minutes per day were 20% more likely to maintain a healthy weight over several decades, reinforcing the importance of sustained exercise for long-term weight management.

British Doctors Study

- Time: 1951-2001

- Size: Started with 34,000 male physicians

- Some Key Findings:

- Lower mortality risk. Doctors who engaged in moderate to vigorous exercise had a 30% lower risk of death from all causes compared to sedentary individuals.

- Better heart health. Regular physical activity reduced the risk of death from coronary heart disease by 40%, even with moderate exercise levels.

Cardia Study

- Time: 1985-present!

- Size: Initially 5,000 black and white young adults

- Some Key Findings:

- Lower coronary artery disease risk. Participants who maintained high physical fitness levels had a 50% lower risk of developing coronary artery disease compared to those with low fitness levels.

- Weight gain and fitness. Individuals who consistently engaged in moderate to vigorous physical activity gained 40% less weight over 20 years compared to inactive participants.

Conclusion? Consistency is Key for Sustainable Weight Loss

If there’s one thing that decades of research across multiple long-term studies make clear, it’s this: consistent physical activity is the #1 best thing you can do for sustainable weight loss. Whether it’s brisk walking, moderate-intensity exercise, or maintaining a regular fitness routine, staying active helps you lose weight, keep it off, and prevent age-related weight gain.

These studies—spanning more than half a century and involving hundreds of thousands of participants—prove that small, sustainable habits add up over time. You don’t need extreme diets or punishing workout regimens.

Take the First Step Today

The real key to sustainable weight loss is two-fold: commit to establishing a routine and commit to finding an activity you enjoy (or can at least tolerate) and access easily.

1. Establish a Routine

Make it specific: Set a clear consistency goal, such as “I’ll walk for 30 minutes every day.”

Identify what motivates you: Whether it’s music, a workout partner, or even something productive like gardening, find something that makes staying active more enjoyable.

Track your progress: Writing things down has been shown to help establish habits. Use whatever works best for you—write it on paper, mark it on your calendar, or log it in a training app.

2. Commit to an Activity

Choose an activity you can realistically stick with—whether that’s walking, cycling, or a simple workout routine tailored to your fitness level. Remember, consistency beats intensity over time, so focus on showing up daily.

If you need help getting started or want fresh ideas to keep things interesting, check out our workout library. It’s filled with easy-to-follow routines for all fitness levels. Start small, stay consistent, and watch your progress grow!

Additional Factors to Consider in Valuing Research

(For readers who want to take a deeper dive into understanding research quality)

Control Group and Study Design

Did the study use a control group? A well-designed study often compares an experimental group (receiving the intervention) to a control group (receiving no intervention or a placebo) to isolate the effect of the variable being tested.

Was the study randomized? Randomization reduces bias by ensuring participants are randomly assigned to groups, making the results more reliable.

Confounding Variables

Were potential confounding factors (e.g., diet, sleep, or stress levels) controlled for or accounted for in the analysis? Studies that don’t account for these factors may draw inaccurate conclusions.

Peer Review

Was the study peer-reviewed? Peer review is a process where experts in the field evaluate the study’s methods and findings before publication, adding an extra layer of credibility.

Statistical Significance vs. Practical Relevance

A study may find results that are statistically significant (unlikely to be due to chance), but are they practically significant? In fitness research, small differences may not translate to meaningful real-world changes.

Funding and Conflict of Interest

Who funded the study? If a study is funded by an organization with a vested interest in the outcome (e.g., a supplement company), this could introduce bias. Transparency around conflicts of interest is important in evaluating the reliability of research.

References

Harvard Alumni Health Study

Paffenbarger, R. S., Jr., Hyde, R. T., Wing, A. L., & Hsieh, C. C. (1986). Physical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumni. New England Journal of Medicine, 314(10), 605–613.

Framingham Heart Study

Dawber, T. R., Meadors, G. F., & Moore, F. E. (1951). Epidemiological approaches to heart disease: The Framingham Study. American Journal of Public Health, 41(3), 279–286.

Nurses’ Health Study

Colditz, G. A., Willett, W. C., Stampfer, M. J., Rosner, B., Speizer, F. E., & Hennekens, C. H. (1987). Weight gain as a risk factor for clinical diabetes mellitus in women. Annals of Internal Medicine, 107(5), 819–824.

British Doctors Study

Doll, R., & Peto, R. (1976). Mortality in relation to smoking: 20 years’ observations on male British doctors. British Medical Journal, 2(6051), 1525–1536.

CARDIA Study

Sidney, S., Jacobs, D. R., Jr., Haskell, W. L., Armstrong, M. A., & Fair, J. M. (1998). Comparison of high- and low-risk young adults: Cardiorespiratory fitness, exercise habits, and coronary risk factors. JAMA, 279(9), 716–722.